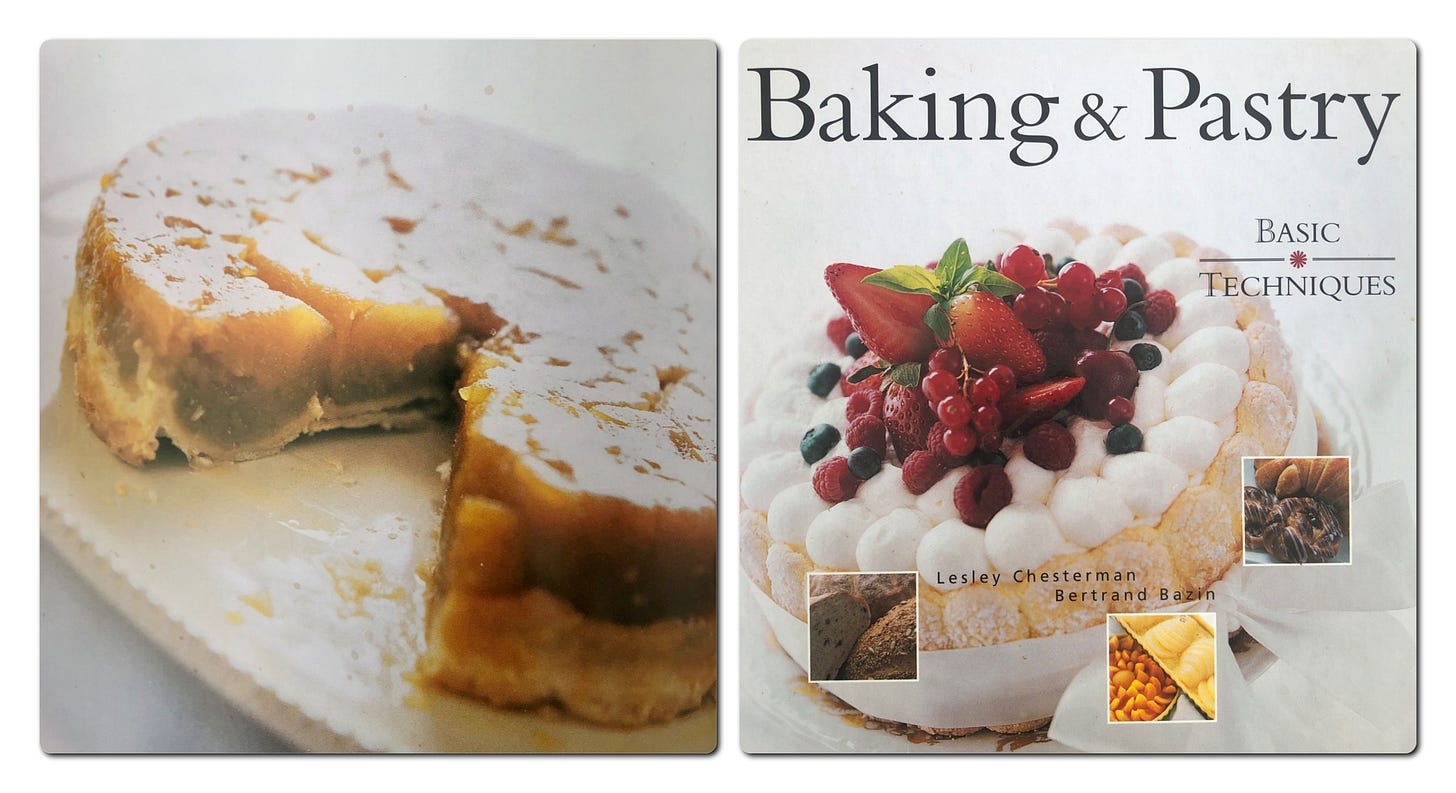

So this week I wanted to write about tarte Tatin for two reasons: 1) apples are affordable and abundant on grocery shelves these days and 2) I recently tried a recipe from a French chef on an Instagram reel and the results were, shall we say, tragic. See below:

This Tatin tragedy irks me for many reasons, beginning with the fact that all my baking instincts were warning me that the French chef’s recipe had TOO MUCH DAMN BUTTER! Also, though many of us try to recreate French recipes, it’s often a losing proposition because French ingredients are different enough to really break a recipe. Their butter is drier (as in less water-logged), their flour is weaker, their apple varieties are vastly different than what we use here. Also, his baking times seemed too short, and as commercial convection ovens are much faster at cooking baked goods, times are sure to be different. So besides the sugar being the same, there isn’t much to go on here.

Also, when I wrote a baking and pastry book in 2000, I included a recipe for tarte Tatin that works brilliantly. So why, you ask, even bother with a new recipe?

Yes, well, exactly. Why, when we have a perfectly fine recipe for something are we always on the lookout for something better? I guess it’s that constant quest we experience in cooking and baking for a moister cake, a flakier crust, a more luscious ice cream, a more chocolatey chocolate cake, etc. And truth is, that hope is kind what makes baking so much fun. But there are limits, and a reliable recipe is a valuable asset in your kitchen repertoire.

There are countless recipes for Tarte Tatin out there and my quest for THE BEST continues. The recipe of the Demoiselles Tatin has been passed down orally so it is impossible to determine the original quantities. The best I ever tasted was in 2000 at Alain Ducasse’s hotel, La Bastide de Moustiers. It wowed thanks to the firm apples that were deeply caramelized, speckled with vanilla seeds, and topped with a crisp (not soggy!) layer of pastry. It was the Holy Grail of tarte Tatins and remains my goal every time I make one.

They key with a Tatin is to begin the caramelization of the sugar before the tart bakes. If you find a recipe that omits this step you should immediately omit that recipe from your life. As for the butter, the French recipe called for 250g whereas my recipe calls for 55g. Your goal is uniformly caramelized apples, not apples boiled in sweet butter.

The choice of apples is also key. I like a high acidity apple like Granny Smith or Golden Delicious, which are less acidic but hold up to baking well. However, Cortland, Spartan or Empire apples can also be used with success.

As for pastry choice, yes a Tatin is commonly made with puff pastry, but puff pastry and moisture do not make for a good mix, so the part of the dough touching the moist apples will end up being a soggy mess. I like pâte brisée for tart Tatin because unless you bake the crust separately and then add it to the baked apples, there will always be some “sog” to the crust, and with pâte brisée you’ll get less.

A final bit of advice about this tart concerns unmoulding. Avoid unmoulding it when piping hot. If you let it cool to room temperature, the caramelized apples will set up a bit and dislodge easily when flipped over. If you want to eat it warm, reheat it a bit once unmoulded. And please, never EVER serve a tart Tatin cold.

Though considered sacrilegious to Tatin purists, I serve the tart with a scoop of vanilla ice cream or spoonful of Chantilly. As for a boozy accompaniment, a shot of Calvados or a single malt is always welcome.

The recipe from my book listed below was found on a sheet of paper wedged into the recipe book of a caterer I worked for in the nineties. The author is unknown but it works extremely well. For now it’s my best but, of course, I’ll keep trying out new recipes until I find a new favourite.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lick my Plate to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.